« I want my next Christ to be the painting that contains more beauty and more joy than anything that has been painted until today. »

Salvador Dalí.

The Christ

1951

Salvador Dalí

Oil on canvas

204,8 x 115,9 cm

Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, Glasgow

© CSG CIC Glasgow Museums Collection

The Christ of Portlligat focuses on one of Salvador Dalí’s most emblematic paintings: The Christ. It is an oil on canvas dated in 1951 from the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum in Glasgow, Scotland. It had not been seen in Spain since 1952, when it was exhibited in Madrid and Barcelona.

The exhibition Dalí. The Christ of Portlligat has been officially opened on 6th November 2023. The event has taken place under the Crystal dome of the Dalí Theatre-Museum, in Figueres. It has been presided over by the Chairman of the Dalí Foundation, Mr. Jordi Mercader, as well as the director of the Dalí Museums and curator of the show, Mrs. Montse Aguer. The third movement of Quartet no. 15 op. 132 by Ludwig van Beethoven has been interpreted by Cosmos Quartet. The director of the Glasgow Museums, Mr. Duncan Dornan, was also present, as well as Infanta Cristina de Borbón, the Mayor of Figueres, Jordi Masquef, among other Patrons of the Foundation, the delegate and subdelegate of the Spanish Government in Catalonia, the general director and the general secretary of the Dalí Foundation, Fèlix Roca and Isabella Kleinjung. The event received the collaboration of the Festival Schubertíada. The exhibition project has been granted the support of ERCO and Fujifilm. Planeta publishing house is responsible for the book Why, Dalí? whose origin is this exhibition.

Exhibition contents

The aim of this exhibition is to show one of Dalí's most iconic works that has not been seen in Spain for the last seventy years. The exhibition project further explores the artist's creative process. It highlights the importance of the landscape and the place where the painting was executed: the Portlligat workshop. It contributes to the works analysis thanks to research carried out both in our own and external funds such as the archives of the Glasgow Museum Resource Centre and the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art.

In addition to the main painting, The Christ, another meaningful work to the artist is exhibited which is closely linked to the previous one: The basket of bread (1945). It leaves its place of honour in the Treasure Room to complement the significance of The Christ and preludes the exhibition installation. Both paintings share the technical mastery, the formal composition, a photographic realism, the chiaroscuro that gives relief to the figure and a light that brings drama to the crucifixion and intensifies its mystical perception.

« For The Christ of St. John of the Cross, I used the same technique and the same artistic texture as for The Basket of Bread, which,

even in its time, represented the Eucharist more or less unconscious. »

Salvador Dalí.

The basket of bread, 1945

© Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, Figueres /VEGAP, 2023

Some unpublished material is also part of the exhibition, that allows you to better understand the context of The Christ: five photographs, six pieces of preparatory material and a notebook with sketches executed between 1948 and 1958. This notebook is shown in original format and on a screen. Also remarkable are two audiovisuals that last 6 minutes and which focus on the relevance of Dalí’s context, the creation process and the landscape.

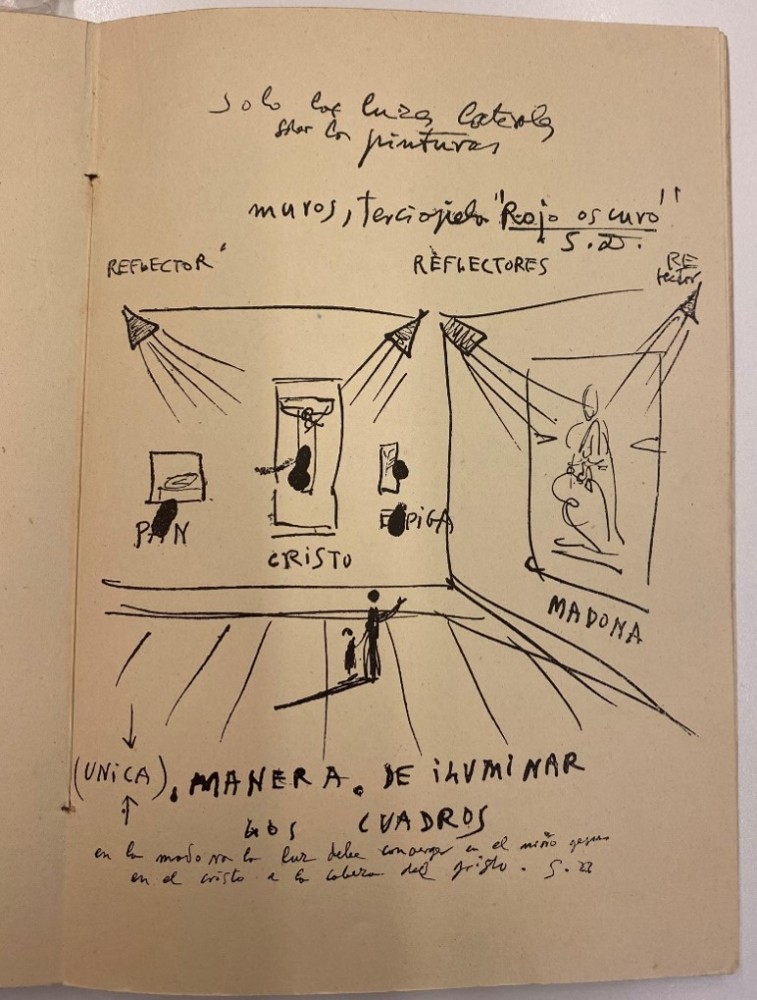

The main piece, The Christ, is shown with a scenography-like installation in order to encourage its contemplation. The red velvet curtain takes on significance because this is the exhibition proposal Dalí projected for the first Hispano-American Art Biennial in 1952.

Letter by Salvador Dalí with instructions on the installation of first Hispano-American Art Biennial in 1952.

The artist hangs The Christ next to The basket of bread (1945), St. George the Dragon-killer (The Ear of Wheat, 1947)

and The Madonna of Portlligat (circa 1950)

Historical and creative context. The Christ as the door to the mystical nuclear period

Salvador Dalí paints The Christ in 1951 in his workshop in Portlligat. He experiments the conclusion of a moment of transformation and also the culmination of his desire to become a classic and the “saviour” of modern painting. The incorporation of religious representations and episodes in his artwork is, together with the postulates of quantum mechanics, a result of the evolution of his thinking. The Christ is the painting that links both moments, it serves as a transition and leads us towards the nuclear mystical periods.

Freud’s theories, together with transcendental discoveries in physics, are in the basis of Surrealism. After the Second World War, however, the Surrealists' attitude towards technological advances changed radically. Unlike Breton, Dalí celebrates the virtues of nuclear physics because it opens doors to the understanding of reality.

It is in this historical context when Dalí and Gala move to the United States, where they live for eight years, until they return to Portlligat in the summer of 1948. They experience moments of uncertainty and change in which the historical events of the mid-20th century shake the European mentalities. As far as Dalí is concerned, he is reformulating his thinking: his interests turn to Heisenberg, nuclear physics and quantum mechanics. As a result of his research and study, the structure of atoms, the disintegration and discontinuity of matter are part of his new lexicon. At the same time, he progressively incorporates religious icons such as the Virgin Mary, Jesus Child and the crucifixion.

We should not read the painter's renewed interest in spirituality and mysticism as a movement of reaction against the previous stage. He knows very well the Spanish mystical poets (Santa Teresa de Jesús and San Juan de la Cruz) and the great masters of the Italian Renaissance. Those are references he combines with an interest in scientific discoveries. He begins a period he calls “nuclear mysticism”, as we can see in the lectures “Why I was sacrilegious, why I am a mystic” (1950) and “Picasso and me” (1951), or in the “Mystical Manifesto” (1951). In this last publication, Dalí writes that nuclear physics defines mystical ecstasy, which is “«superjoyful», explosive, disintegrated, supersonic, undulatory and corpuscular, ultra-gelatinous, because it is the aesthetic hatching of the maximum of paradisiacal happiness that human being can have on Earth”.

Dalí declares that his new kingdom is the soul and that he sees in religion and the love of God the only hope for humanity. Dalí will address one of the key themes of Christianity: the crucifixion of the one who must save humanity. He states: “I paint in a constant explosion. In a nuclear bombardment. From a scientific point of view, it is possible to approach the true mystery of life”.

A journey to Glasgow

The reason why The Christ ends in Glasgow has an indisputable protagonist: Tom Honeyman (1891-1971), director of the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum and responsible for the acquisition. Honeyman has a lot of experience in the art world, he knows about Dalí’s artwork and admires it. In December 1951, he visits the exhibition of Dalí’s Christ at the Lefevre gallery in London and is impressed by the painting: “Still bewildered, I returned to the painting and the crowd. My main difficulty was how to marry the theme of the painting with Dalí's philosophy of art and public statements as I remembered them. [...] The painting seemed from another time: a work of shameless romanticism in an era of eclectic classicism”. The acquisition of the work is not without controversy. After several negotiations with Salvador Dalí, the work and its rights are bought by the city of Glasgow for a high sum at the time, 8,200 £, a fact that generates strong controversy among Scottish citizens, who claim money should be invested in exhibition spaces for local artists. However, Dalí’s Christ becomes an “artistic event” in the city. As Honeyman himself informs Dalí, Glasgow “had a glorious summer with your painting”.

In 1961, a visitor to the museum attacks the painting by throwing a stone to the canvas and forces it to be removed and restored. In 1993, The Christ moves temporarily to St. Mungo Museum of Religious Life and Art in the same city until, in 2006, with the reopening of the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, it returns to its original location. Since 1965, the work has only been loaned on limited occasions.

Dalí explains himself

The Scottish Art Review, in its first issue of 1952, precisely dedicated to The Christ, includes a letter from the artist about the painting that has just been sold. Given the expectation raised by the purchase, the editor considers it appropriate to publish an article by Dalí: "The position of the Christ ─angle of vision and inclination of the head─ has caused one of the first objections to this painting. From the religious point of view, this objection is untenable since my painting was inspired by the drawing in which Saint John of the Cross represented the crucifixion. In my opinion, this drawing ─the only one the saint ever made─ had to be made as a result of an ecstasy”. And he continues, “the first time I saw the drawing I was so impressed that, later, in California, I saw Christ in a dream in the same position but in the landscape of Portlligat, and I heard voices saying to me: “Dalí, you must paint this Christ”. I started painting it the very next day. When I began the composition, I intended to include all the attributes of the crucifixion—nails, crown of thorns, etc.—and to transform the blood into red carnations nailed to the hands and feet, with three jasmine flowers springing from the wound on his side. These flowers would have been executed in the ascetic manner of Zurbarán. But just before finishing the painting, a second dream changed everything. [...] I saw my painting again without the anecdotal attributes: nothing but the metaphysical beauty of the God-Christ”.

Dalí responded with these words: “My aesthetic ambition, in this painting, was completely opposed to that of all the representations of Christ painted by the majority of modern painters, who have interpreted him in the expressionist and contortionist sense, thus provoking emotion through ugliness. [...]. The geometric construction of the fabric, in particular the triangle in which Christ is inscribed, has been obtained from the laws of the Divine Proportione by Luca Pacioli”.

References and models

In terms of technique and style, The Christ's references are the Spanish painters Alonso Cano, Francisco de Goya, Francisco de Zurbarán and, above all, Diego Velázquez. The latter, the greatest exponent of Spanish Baroque painting, is a constant in the work of the surrealist artist. Salvador Dalí, following the example of Velázquez, sets out to create a work different from that of his contemporaries. He paints a calm and dignified Christ, of whom we don’t see his face or visible wounds: “Precisely because I have gone through cubism and surrealism, my Christ it is not like the others, without ceasing to be classic. I think he is at the same time the least expressionistic of all those that have been painted today. He is a beautiful Christ, just like God.”

To materialize this idea, he looks for a model that represents the culmination of Apollonian beauty. Thanks to the professional relationship and friendship with American film producer Jack Warner, he meets who will become the model for the Christ, a Californian gymnast and action film specialist Russ Saunders. As a film specialist, Saunders had participated in films such as The Three Musketeers (1948) or Singing in the Rain (1952).

In addition to sketches done with the model, the artist also uses photographs to transfer the model’s body to the canvas. It is thanks to the unpublished negatives by Weiman & Lester, preserved in the Dalí Foundation archives, that it has been found that, a part from Saunders, another model participated, who has not yet been identified.

Weiman & Lester Photo Services

Photo session with Russ Saunders

Method and work techniques

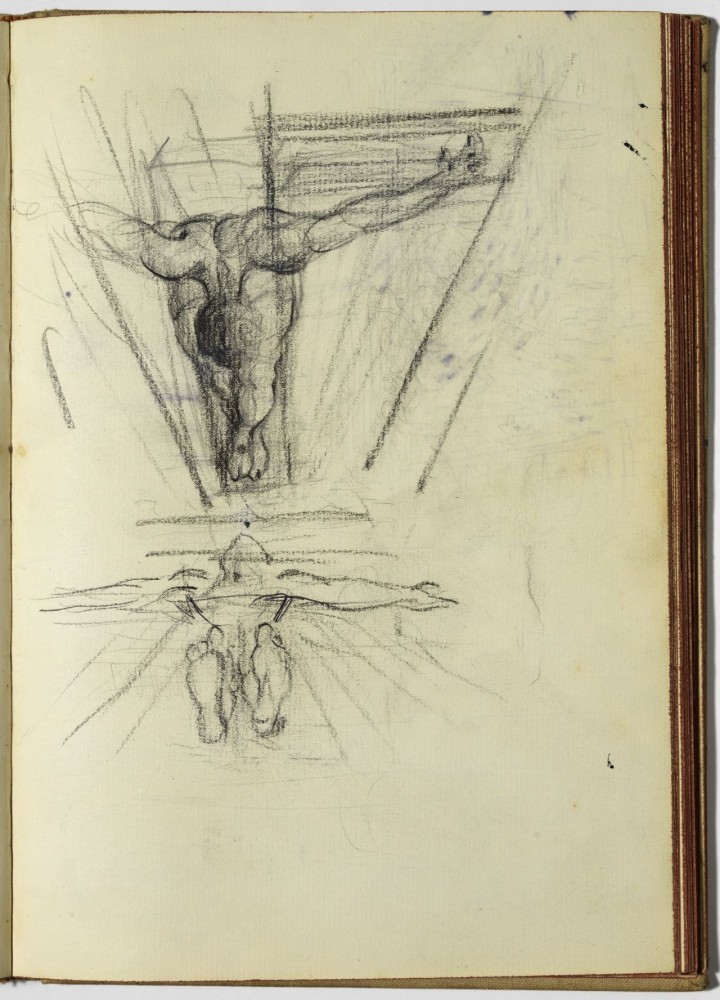

Dalí's working process is complex. He is a hard worker and meticulous; he uses a lot of technical resources to achieve the definitive painting. First, he carries out numerous sketches and drawings on different papers and notebooks. In a second phase, he searches for the most suitable models, he takes pictures of the and draws them. Finally, he transfers this material to the painting. It is an organic process that follows in the footsteps of the classical tradition, despite using his own resources derived from the use of new materials and techniques of the time.

This exhibition shows an unpublished sketchbook from the Pere Vehí Archives, in Cadaqués. It provides valuable information on the work process of several projects, among which are The Christ but also Christopher Columbus (1958) or The Sacrament of the Last Supper (1955), or projects such as the graphic script for in the unpublished film L’ànima (The Soul, 1948-1952). These projects allow us to date the sketchbook in the beginnings of the nuclear mystical period, between 1948 and 1958. We see an artist who rehears forms, arranges elements, perspectives, and compositions - some of which recall the figure sketched by mystic Saint John of the Cross─, until he finds the most suitable ones.

The page of the unpublished sketchbook of Pere Vehí

Dalí usually uses objects and people as models that are close to him, physically and emotionally speaking. Thus, in some of his works we recognize characters from Cadaqués, often fishermen. In the case of The Christ, the landscape is completed with an everyday scene: fishermen working on the shore. However, for this particular painting, Dalí chooses figures of a very specific origin: “I had also been tempted from the start to take as a model, for the background, the fishermen of Portlligat. But in that dream, in the place of the Portlligat fishermen, appeared, in a boat, a character of a French peasant painted by Le Nain, whose face alone had changed to resemble a Portlligat fisherman. The fisherman, seen from the back, had, however, a silhouette in the style of Velázquez.”

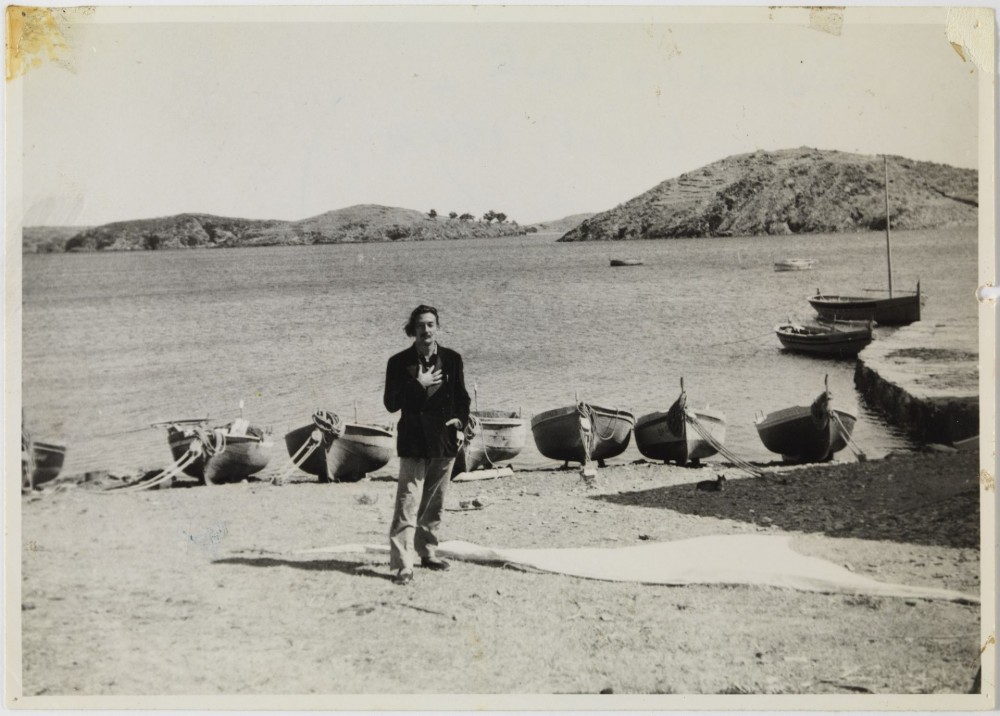

The landscape: Portlligat Bay

For Dalí, the landscape of Portlligat is the one that shapes his world. A world that, during the years of exile in the United States, he knows and paints by heart and where, after eight years of absence, he wants to return. The landscape of Portlligat and Cape Creus are one of the elements that have shaped the artist's personality and emotions: "I need the localism of Portlligat like Raphael needed that of Urbino, to reach the universal by means of the particular”. This spot in the Costa Brava was not only his residence next to Gala for fifty years and his most stable workshop, but it also gave him a specific way of living and understanding the world.

Salvador Dalí in Portlligat Bay, 1954

Image rights by Salvador Dalí reserved. Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, Figueres, 2023

Programme

On the occasion of the exhibition, the Dalí Foundation has organized four speeches that will be held in the old scene of the Dalí Theatre-Museum every Thursdays of November. The curator of the exhibition, Montse Aguer, will talk about the relevance of The Christ. The deputy director of Collections and Exhibitions, Carme Ruiz, will relate the painting to Santa Teresa de Jesús. Both the head of Conservation and Restoration Irene Civil and conservator-restorer Laura Feliz will explain the peculiarities of the Christ's work process. Finally, Eva Sanahuja, head of projects at ERCO, a company that has collaborated in the exhibition lighting, will comment on how a temporary exhibition is lit.

Book Why, Dalí? by Planeta publishing house

The book WHY, DALÍ? The enigma as a provocation in art investigates the reasons why Dalí created The Christ. It is a different and innovative approach to Dalí and one of his most iconic and enigmatic paintings, on the occasion of the first exhibition specifically dedicated to this pivotal piece. Its authors are the writer Javier Sierra, the painter Antonio López, the director of the Dalí Museums, Montse Aguer, the director of the Glasgow Museums, Duncan Dornan, and its curator Pippa Stephenson, as well as members of the Dalí Foundation Carme Ruiz, Irene Civil, Laura Feliz and the head of Documentation Rosa M. Maurell.

By means of a fiction in the form of an epistolary correspondence with the painter, Javier Sierra immerses us in the essence of this work and the creation process through a disturbing question: Why, Dalí? Then, Antonio López, in dialogue with Montse Aguer, elaborates on the figure of Salvador Dalí and invites us to delve into the mind, brain and creative process of one of the most complex artists of recent times.

Cover of the book Why, Dalí? published by Planeta and the Dalí Foundation

Javier Sierra is a Planeta award winner. He is passionate about the mysteries of art. Several of his works are closely related to this, such as The Secret Supper (translated into more than 40 languages), The Master of the Prado or The Invisible Fire. In a cryptic way, he claims that he discovered Dalí during an ecstasy in front of the paradise of Bosch's The Garden of Delights, and that, since then, he has not stopped watching him with growing admiration and surprise.

Antonio López is one of the most relevant painters and sculptors on the international artistic scene. Throughout his career he has received numerous prizes: the Prince of Asturias Arts Award and the Velázquez Visual Arts Award. His career, since the sixties, is full of numerous collective and solo exhibitions in Spain and abroad. He has always considered Dalí as one of the most interesting and influential figures in contemporary figurative art.

Mounting

The exhibition Dalí. The Christ of Portlligat, which is on show from today 25th October until 30 April 2024, has Montse Aguer as curator, the general coordination by Carme Ruiz, Rosa Maria Maurell and Lucia Moni, and has the special collaboration of the Conservation and Restauration departments and the Centre for Dalinian Studies. It also counts on the contribution of the Museums, Digital Transformation and Rights departments. The Dalí Foundation wants to thank the unvaluable collaboration of the Glasgow Museums, which have loaned one of their most precious pieces and have contributed to writing Planeta’s book. 3carme33 is in charge of the exhibition mounting design, the typo design is by Alex Gifreu. Two audiovisual projects have been made by David Pujol, Jordi Muñoz as editor and Òscar Xavier Gómez as projectionist. The show has also benefited from ERCO and Fujifilm support.

Website devoted to the exhibition contents: https://salvador-dali.org/expoDaliCrist